History Notes On – Caste System In Ancient India – For W.B.C.S. Examination.

ইতিহাস নোট – প্রাচীন ভারতে বর্ণ প্রথা – WBCS পরীক্ষা।

The origins of the caste system are not clear. It is generally agreed that a division of labour came about as a result of the growth of an agricultural society and villages when the new ethnic element was introduced in the indigenous population of the day with the arrival of the Indo-Aryans. An element of race (and colour of the skin) no doubt played a part in the social divisions that emerged.Continue Reading History Notes On – Caste System In Ancient India – For W.B.C.S. Examination.

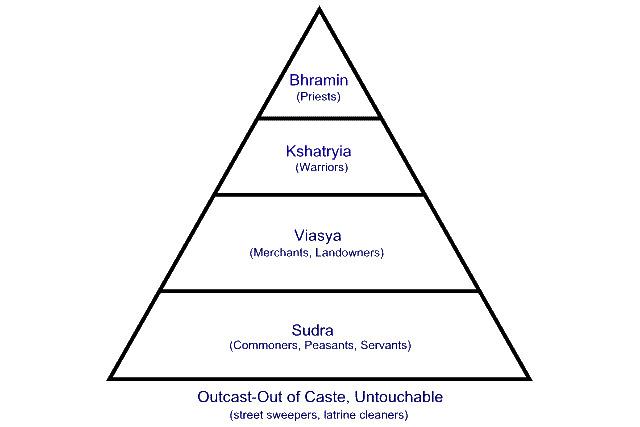

The chatur varna system was created and it is generally believed that the Indo-Aryans emerged as the custodians of knowledge (brahmana) and the defenders of territory (kahatriya) while the others were assigned the lower status of vaisya and sudra with the work of cultivation and manufacture of artisan goods. Unclean jobs— treating the dead bodies of animals, for instance— were for the lowest strata of society and described as ‘exterior’ castes, or outcastes.

Division of labour is not unique to India; what is unique to India is the institutionalisation of this division of labour into the rigid system of caste so much so that a vocation became a fixed hereditary trait of a family. In due course of time, the Varna system acquired the features of a class division. The brahmin and kshatriya emerged as the upper classes. However, caste is not class, as mobility from one caste to another is not possible.

It is the Rigveda that is cited as the earliest source for mention of the caste system in India. The Veda mentions brahma, ksatra and vis as groups representing priests, kings and rulers, and the common people, respectively. The ‘Purusasukta hymn’ describes the brahmana, rajanya, vaisya and sudra as emanating from four parts of the body of the creator.

In the post-Vedic period, the brahmanas became powerful and dominant, laying down the rights and duties of the castes in the caste hierarchy. The Bhagavad Gita of the Mahabharata, ascribed to this period, upholds the caste system as laid down at this time based on the concepts of guna, dharma and karma. Some of the features of the caste system were a rigid hierarchy of castes and sub-castes; endogamy; occupational associations; distinct dress, speech and habits of each caste; rituals, and privileges and disabilities specific to the castes.

Even as the caste system flourished in Hindu society, the rise of new religions, Jainism and Buddhism, questioned the basis of the caste system and were opposed to it. The Bhakti movement that gained prominence in the medieval period opposed caste ideology. The saints and poets of the Bhakti movement came from different castes and the movement appealed to people of all castes.

The followers of Vallabha, Chaitanya, Kabir, Guru Nanak and others were from different castes who mingled in devotion. In the modern period, there were many social, religious and cultural reform movements like the Brahmo Samaj in Bengal, the Arya Samaj in Punjab and the Ramakrishna Mission that aimed at emancipation of the people from the rigid values and practices of the caste system.

Economic associations link the castes in a village or a group of villages. The peasant castes are predominant in villages. The servicing castes (barber, washerman, carpenter and cobbler) provide service to the village community. Artisan castes produce goods that are wanted by the people of the villages. A village need not necessarily have all the caste communities that produce different types of work, in which case there is reliance on other villages for certain services or goods.

There are relationships between caste groups that are marked by the features of caste hierarchy. For instance, the artisan and servicing castes perform additional duties during marriage and other events, for which they are paid in cash and kind. What resulted was castewise division of labour coupled with enduring ties between castes and pervasive ties that even cut across the strict caste relationship. Ritual occasions and festivals and social functions celebrated by the village as a whole required cooperation of various castes.

The functioning of the village community as a social and political entity required that the castes reside in amity with each other. In other words, there are the ‘vertical’ (local) ties between castes that strengthen the caste system even while forging a stronger bond between castes within the village community. The caste system with its inherent inequalities produced a much stratified society but the village continued to function effectively as a community.

Caste to this day determines, in large parts of the country, the pattern of social interaction and commensal relations, i.e., whether food or water may be accepted from a member of a certain caste, as Aijazuddin Ahmed observes in his Social Geography.

Please subscribe here to get all future updates on this post/page/category/website

+919674493673

+919674493673  mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in